Recently a question was raised on NextDoor about why new homes continue to be constructed when we’re in the middle of a multi-year drought. It’s a great question and sparked a lot of discussion. These are some thoughts on the topic and how it relates to the principles we’ve embodied in our government based on my years as an elected official1.

Most of us accept the concept of “first come, first served” as a guiding principle in group interactions. Anyone who cut in front of a long line of people waiting to complete their purchases at a store would learn, first hand, how quickly a group of polite individuals can turn into an angry mob.

So why don’t we simply stop new construction during droughts? Why are we allowing new people to cut in front of existing consumers of water?

The long answer is no doubt more involved than what I’m going to describe here because water law is extremely complex. In fact, there are two distinct bodies of water law in the United States, the old/eastern one based on English law and the new(er)/western one which grew up as the nation expanded. You may be surprised to learn some of the most contentious, and difficult, Supreme Court decisions throughout our history have involved resolving water disputes in the western, more arid part of the country.

When government doesn’t do something obvious some immediately conclude incompetence, inefficiency or corruption is involved2. Granted, history shows those things do occur. But they’re far less common than many people think. Instead, the failure to do something obvious is generally the result of how our principles of government interact with each other. In other words, the lack of action is usually by design. As software engineers like to say, it’s not a bug, it’s a feature…at least in the vast majority of circumstances.

The guiding principles involved are individually both simple and, in most people’s eyes, laudable3:

- How private property is used can be regulated. But government can’t act as an owner/controller of private property without paying for the right to do so (usually by purchasing it at its current market value).

- Government must treat everyone equally.

- Government actions must be reasonable and based on objective evidence.

- Government regulations must serve an objective/definable public good.

- Emergency rules can only be adopted in objectively-defined emergencies, and must be for a limited period of time.

That second principle undercuts first come, first served. Consider the example of Long Standing Homeowner objecting to New Comer building a two story house on New Comer’s property because it will shade Long Standing Homeowner’s pool. The regulation governing home heights could have restricted everyone to a single story. But the community, through its government, decided to allow two story homes. Having done that, New Comer must be allowed to build a two story home, even though it shades Long Standing Homeowner’s pool. Forbidding construction would violate the treat everyone equally principle.

The community might be able to establish a regulation about limiting shading stuff on your neighbor’s property, based on the argument that too much “undesired” shade makes the community less desirable and community members less healthy4.

But if it did Long Standing Homeowner might well have found building his pool more difficult. Because the community would’ve then had the authority to regulate where he or she put the pool since its location puts a constraint on what the owner of New Comer’s property can do. Even though New Comer hadn’t yet purchased the property, somebody owned it, and they have to be treated equally before the law, too. Including not having the future use of their property unreasonably constrained.

But clearly droughts harm everyone and government’s biggest responsibility is to protect the community and community members. Even if we can’t use the first come, first served principle why can’t government stop the harm inevitably caused by a shrinking pool of a vital resource?

The answer is it can and does…but it has to be done through regulations which must be reasonable and objective. Defining what’s reasonable is (pun intended) reasonably straightforward because the determination mostly relies on maintaining consistency with what other laws, regulations and our constitutions require.

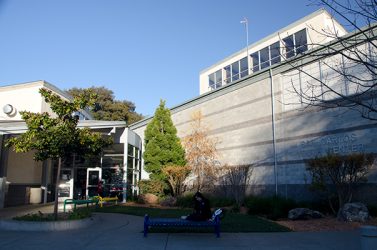

All communities, so far as I know, have limits on development based on how much water they have access to. East Palo Alto, for example, is one that I know for a fact does. Others, like San Carlos, don’t appear to have limits…but that’s because San Carlos’ allotment of Hetch Hetchy water is quite large5.

Defining an objective basis for any new rule limiting private activity – defining why we want a particular new constraint – is surprisingly hard. It’s particularly hard for risks we think we’ll face in the future because figuring out what the future holds is beyond our abilities. We have no Cassandras6 to tell us, definitively and presumably objectively, what’s going to happen.

Even though we know we’re in a drought and we know we all need water it’s equally true (or at least has been so far) that droughts pass. And there are other ways of addressing the so far short term damages caused by droughts: water conservation7, regulations requiring more water efficient building designs (e.g,. low-flow toilets and shower heads), etc. Given all the available alternatives it would not be reasonable to issue a blanket constraint on new construction. It wouldn’t be objective in the face of the facts we know8.

That’s why you see a tightening of rules as droughts persist and intensify. Many of those rules stay on the books – they’re not structured as emergency regulations – to help reduce the impact of the next drought. Others, of an emergency nature – “you can’t water your lawn” – are in place only for objectively-defined periods of time, and generally come later, as a drought gets bad and lingers, because they represent a higher level of regulation of private interests.

We just saw how all of this operates courtesy of Covid-19. Reaction to the virus’ impact took time, and the emergency actions which were ultimately taken to preserve public health and safety were for limited periods of time and based on objective data. Note that gathering objective data for something new, like COVID, is hard and takes time…during which public policy still needs to be made. Such policies are subject to rapid change and, since the public doesn’t generally like rapid change, government response is further delayed.

We also saw something else: strong legal opposition to those regulations. In some cases that opposition succeeded in rolling back or modifying them. This, too, is a necessary part of our system of government. One of the ways we ensure regulations are reasonable and objective is by allowing individuals to argue they are neither in court and have the court overturn or constrain the regulation.

Given that the first rule of American politics is “follow the money”9 you can imagine how quick and how forceful the challenges would be to banning, even temporarily, new construction10.

Doing so would interfere with the private interests of a lot of people and economic power…both of which translate into political and legal power. In the earlier stages of a drought such challenges would almost certainly be successful. Which would nullify the bans and stick the communities who promulgated them with enormous legal bills and fines to boot.

I don’t mean to imply nothing can be done about droughts. That’s not true. And beyond the things that we already know how to do, and have done11, the community does have the power to make even “tougher” rules if we can show, objectively, that droughts are getting worse and/or more frequent12.

We can also come together to pursue other public responses. More reservoirs, if climate change makes California, on average, wetter as well as warmer, to store water for dry years. Constraints on commercial crops that consume a lot of water13 Encouraging or subsidizing recycling potable water or desalinization14. Just to name a few (I’m sure you have your own ideas).

We just can’t impose constraints that are unreasonable and/or not based on objective evidence. We have decided acting based on a whim or a fear is unacceptable to the community15…and chosen to prevent our government from doing either.

translation: please always remember I’m not a lawyer ↩

It’s fascinating a culture which espouses the principle someone is innocent until proven guilty so often doesn’t bother to do the admittedly hard work of trying to figure out why something didn’t work out the way they expected it to involving the operation of government. But that’s a topic for a different article. ↩

which is why they’re the principles we have our government use ↩

I’m speculating here. But I’m confident such a rule would be difficult to define because I don’t know of any communities that have such a rule. ↩

Fun fact: it’s large because the Hetch Hetchy pipeline runs through San Carlos, and the community, or its predecessors, were “bought off” to approve construction of the pipeline by being given a significant piece of the action. ↩

and a good thing, too, for any would-be Cassandras, because the Trojans killed her for accurately predicting the fall of Troy. But that’s the thing about gifts from the gods – they generally come with nasty side effects. ↩

either voluntary, through raising the price of water, or by reasonable regulations ↩

As opposed to the facts we fear may come to pass. But fears are by their very nature not objective. ↩

It’s also rules #2 through #5. It’s only when you get to rule #6 that other things start to apply. Just sayin’. ↩

An interesting side note: my wife and I built a new home in San Carlos seven years ago. Our new home comes with thousands of dollars worth of hurricane clips to secure its roof…even though there’s been only one reported siting of the kind of storm which would necessitate them – a tornado – in recorded San Mateo County history. But there are relatively few people building homes at any one time and the cost, while potentially unnecessary, is small relative to the overall cost of construction. So the political power to oppose such regulations didn’t coalesce when they were promulgated and they got incorporated into law. ↩

conservation regulations, emergency decrees ↩

Personally, I wouldn’t be surprised if bad droughts won’t be with us as a result of how badly we’ve screwed up the global climate. And always remember there is evidence the last few centuries have been unusually wet in much of the western United States. ↩

Much of California’s agricultural output is for “snacks”: things like almonds, grapes for wine, etc., which are tasty and fun but hardly necessities of life. ↩

Or my personal favorite, figuring out how to pilot icebergs from Antarctica to California. Think how cool it’d be to see an iceberg cruise under the Golden Gate Bridge! Plus, we could maybe ski on it as it melted to supply us with water (thanx to author Jerry Pournelle for this one)! ↩

Although such actions do happen. Consider Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus — “produce the body if you’re going to charge this guy with a crime” — and FDR’s establishment of internment camps for Japanese-American citizens. But the first was granted a narrow endorsement by the Supreme Court due to the extraordinary nature of the Civil War and the latter is a mark of shame we still bear and led to compensation for the victims. ↩