Occasionally, I get really interesting emails from people about what appear to be simple topics but are actually related to much broader issues of governance. That was the case with one I got from 4th grader Lucia of Arroyo Upper Elementary. Her email — which was very comprehensive, and well thought out — started with a simple question:

I am very concerned about new stores and restaurants moving in and out from San Carlos. In particular, we’ve lost our bakeries. I am concerned for the following reasons; bakeries provide healthy food, bakeries provide affordable food for children and seniors especially, and healthy cities depend on having a balance of restaurants. Fresh bread made without a lot of preservatives and chemicals is especially important for a healthy city. Can you please do work on attracting good bakeries to San Carlos?

Her email went on to raise a fundamental question about government: to what extent should it dictate the structure of a community? My reply appears below.

You raise good points about the way local government helps create the community that residents share, Lucia. But there are limitations, both legal and practical, on what local government can do which you may not be aware of, and which I’d like to describe for you.

All governments exist for a simple purpose: to define the structure which allows people to live together in a community. Humans are remarkable animals, with the ability to override their built-in “programming” – that’s a big part of why we send all our young to school, for years, to learn how to do that – but we still have that built-in wiring. San Carlos is about 4 square miles in area, and is home to about 30,000 people. Imagine what it would be like if it was populated by 30,000 Bengal tigers: soon enough, there probably wouldn’t be any tigers at all, because they’d fight each other to the death! Conversely, San Carlos could probably host billions of ants, not just because they’re individually tiny, but also because ants have evolved to live and work together naturally in large groups.

Humans occupy a middle ground. We are very individualistic…but we are also evolved to operate in groups, as families and tribes. For most of our existence as a species, that’s how we lived: families that were part of tribes, which co-existed, sometimes peacefully and sometimes not. There weren’t ever very many of us. In fact, there’s some evidence (in our genes) that we almost went extinct.

That all changed about 10,000 years ago, when our ancestors figured out how to grow crops and raise animals for food (e.g., meat, milk, etc.). Suddenly, it became possible for a lot more humans to live in certain areas than was ever possible before. But that forced us to figure out how large numbers of highly-individual-but-able-to-cooperate-animals could live together. We needed an organizing principal bigger than tribes.

We found it by creating government (some would argue that we created religion first, and government shortly thereafter). Government was the framework by which we established rules that all of us living in a certain area would follow. That allowed large numbers of humans to live together. Not always peacefully. But well enough that the benefits of having large communities began to appear. Those turned out to be enormous: when not everyone needs to know how to do everything to live, we can benefit ourselves – that’s our individualism at work – by specializing in different things, and selling the results to each other (that’s our social nature at work).

Government didn’t always come into existence fairly, or peacefully. As you’ll learn by studying history, humans all too often are willing to use violence on each other to control the rule-making process. But the basic idea worked: by establishing rules that govern how humans live together, more humans are able to live in an area than would otherwise be possible. It’s a vitally important, but generally unappreciated, role of government. One of the people who helped create the United States government put it this way: if government can’t make it possible for people to live and work together, it pretty much doesn’t matter what else it can do.

Once you discover the idea of creating rules to allow people who are not part of the same family or tribe to live together, there’s a natural follow-up question: how many rules should you create? And who gets to create them?

Humans have explored, and are still exploring, all sorts of different answers to those questions (one of the reasons I love history is because I love reading about all the things that have been tried, and how they have, or have not, worked out).

In the case of the United States of America, I would argue that our answers are these: as to how many rules should you create, as few as you can; as to how they get created, by people selected by the community.

The first answer – as few as you can – is both a reflection of our desire to maximize individual freedom (the ability to live your life as you wish to, not as someone else tells you to) and a recognition that we will all have much more “stuff” to sell each other if we maximize individual freedom. This is generally referred to as the “public versus private” sector split. The public sector – the government – sets the rules, but then gets out of the way to let the private sector – individuals acting as themselves, or in groups – do its thing.

The second answer – choosing rule-makers by the community being governed – is why we hold elections for jobs like being a city council member, or Governor of California, or President of the United States. It’s based on the common sense idea that most people can do a decent job of making public rules…if they commit the time to study the situation the rules are intended to govern. Rather than make everyone weigh in on the design of every rule, we choose a smaller group of people to make the rules, and delegate our individual rule-making “power” to them. But we define the limits of what they can decide, and require them to be re-selected – re – elected – periodically, to keep them from making rules that only benefit themselves, their families, and their friends.

So how does all this relate to the closing of Le Boulangerie and bakeries in San Carlos?

The city government doesn’t pick which businesses operate in our town. Instead, we establish rules about how businesses must behave, and, sometimes, how many of which kinds of businesses can operate in a given area. For example, we have rules limiting the number of banks, nail salons, and low-price discount stores that can operate along downtown Laurel Street. But we don’t choose which banks or nail salons come to town, and we don’t require a minimum number of banks or nail salons. Instead, we let the private sector decide what businesses to open. If a bakery wants to open, and it’s willing to follow our rules, we allow it. If another bakery wants to follow our rules and open, we’d allow that, too…even if the second bakery caused the first bakery, or both bakeries, to go out of business because there wasn’t enough interest in baked goods.

And if no one wants to open a bakery, we allow that, too. Why? Because maybe the community would rather have, say, a skate shop or another restaurant in the space the bakery would occupy. If that’s the case, our “forcing” a bakery to open would interfere with the desire of individuals to do business at a skate shop or dine out at a restaurant. We don’t want the public sector to interfere to that extent with private, individual choices.

Communities sometimes do encourage certain kinds of businesses to open. You could imagine a somewhat isolated community, say, encouraging a grocery store to open in town so that community members wouldn’t have to drive 50 miles to buy food. But they don’t require a grocery store chain to build them a store (in fact, I don’t think the United States or California legal systems even allow such an action by a community). Instead, they establish incentives, bonuses, to induce someone – some private individual or organization – to build a store. Occasionally, communities will force a business to close in order to make way for a new store. But if they do that, they have to buy the business being forced to close from its owners. That’s because we’ve decided the public sector – government – shouldn’t have that kind of unfettered power.

So what does all this mean for your desire to see a new bakery in San Carlos?

To me, it suggests several things. You could recruit a bakery to come to town, by visiting nearby bakeries and telling them how much business they could do in San Carlos. Going along with that, you could organize other community members to do the same thing: the more people in San Carlos talk publicly about how much they’d love to have a bakery, the more likely some bakery will hear about it, and decide they want to open a store in San Carlos. This could also involve contacting the San Carlos Chamber of Commerce – a private organization of local businesses – about the desire for a bakery, and perhaps some of the people who own commercial property along Laurel Street (I’ve copied the chief executive officer of the Chamber, Dave Bouchard, on this reply so you can reach out to him, and I’ll send you contact information for a couple of the major property owners in town after I get their permission to introduce you to them).

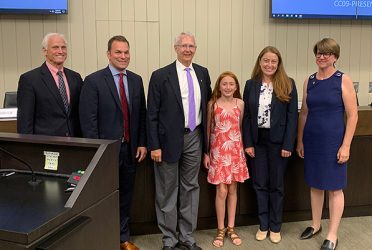

You could also lobby the City Council to create an incentive for a bakery to come to town (I’m not sure the Council has the legal authority to do so, but it might, and, either way, that doesn’t prevent anyone from lobbying for the Council to consider creating an incentive). If not enough Council members want to do that, you could push to elect new Council members who share your views on the importance of bakeries to community life. In fact, this year is a great time for you to do this, because there will be three new Council members elected (three of my colleagues have decided not to run for re-election; the three candidates I know are Adam Rak, Sara McDowell, and Laura Palmer-Lohan). You could lobby all the candidates about the need for a bakery, and try to get them to commit to encouraging one to come to San Carlos (I’ve copied the three candidates I know about on this reply, so you can reach out to them).

Personally, I would not support creating an incentive program for new bakeries. Why? Because I believe such choices are best made by the private sector – individuals encouraging a bakery to open. Put another way, rather than “vote for a bakery Council member” I’d rather people “vote with their wallets”, and make it known that San Carlos really wants a bakery. In that sense, I think the first set of actions I mentioned are better than the second. Why do I feel that way? Well, for me, it’s one aspect of “have fewer rules, and let individuals make their own choices whenever possible”.

Thanx for reaching out and contacting the Council about your concerns, which I felt were very well expressed. Thank you, too, for giving me a chance to send you this lengthy reply; I hope you find it enlightening.

And given your interest in governance at such a young age, please consider getting involved in politics as you get older. All too often people think community leaders just appear out of nowhere. But the truth is, they grow out of individuals who care about the health and well-being of their community. Like you.